320 Spadina Avenue, not to be confused with 320 Spadina Road, that was Jeff Healey’s recording studio, Forte Records—not my apartment, but we did receive his mail quite frequently.

It was 1998 and from the street 320 could not be easily located. Our unofficial neighbour concealed our entrance from dawn to dusk: a friendly old guy with a shopping cart full of cheap plastic toys he sold for cash without a permit. The pedestrian traffic came to a halt right in front of 320 as the wide sidewalks were cluttered by the additional outdoor aisles of the exotic fruit shops, restaurant supply depots, produce markets and illegal vendors selling herbs and trinkets atop cardboard boxes. On occasion a monk would sit on a folded blanket in the thick of the bustle across from the door, playing his flute and garnering the deepest respect from the elders who placed their coins in his old copper singing bowl. All of this visible from my third-floor bedroom window.

There was so much confusion about our address, we started using 318 because it was the only number you could locate from the street.

Once inside the ground floor door, you would immediately be assaulted by the stink of raw sewage, rotting flesh, dirty socks. Durian, the world’s smelliest fruit, it’s banned from some public spaces in southeast Asia, but not 320 Spadina. Everyone who visited became quickly educated on durian, but we couldn’t really figure out why the smell landed inside our building when the fruit shops were several doors over. Someone was even nervy enough to bring it to a party we once hosted. It tastes like custard, but only if you can get past the smell.

At the top of a long staircase was our door, which opened onto another steep and narrow set of stairs. Once inside, the apartment was a sprawling space of rooms opening off the hallway that was as long as the building was deep. The two front bedrooms looked over Chinatown, which was never quiet. A bustling foreign market in the heart of the city by day, and a parade of monstrous mobile trash compactors by dusk. Daily. For hours. So. Much. Garbage. Guests would toss and turn all night at 320, especially in the winter when the radiators squealed their high pitched announcement of the oppressive heat—and accompanying dryness—guaranteed to make the inside of your nose swell until it too squealed as your breath laboured through its narrowed passages. The windows had to remain open, we wore shorts year ‘round and the street noise quickly became our lullaby.

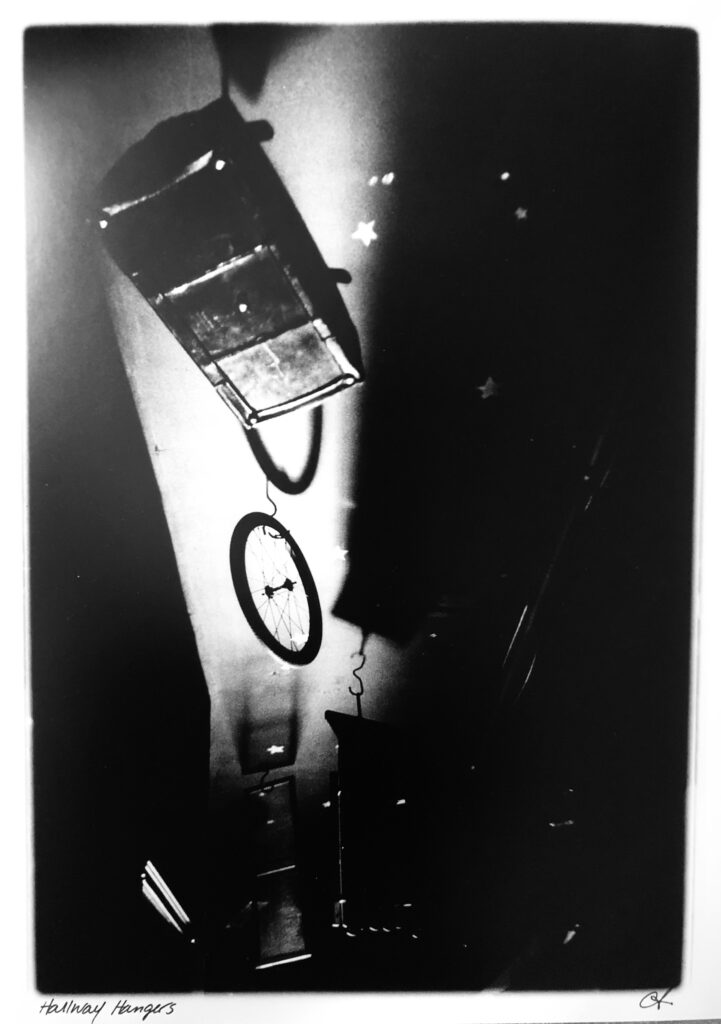

320’s hanging gallery of random items in the hall.

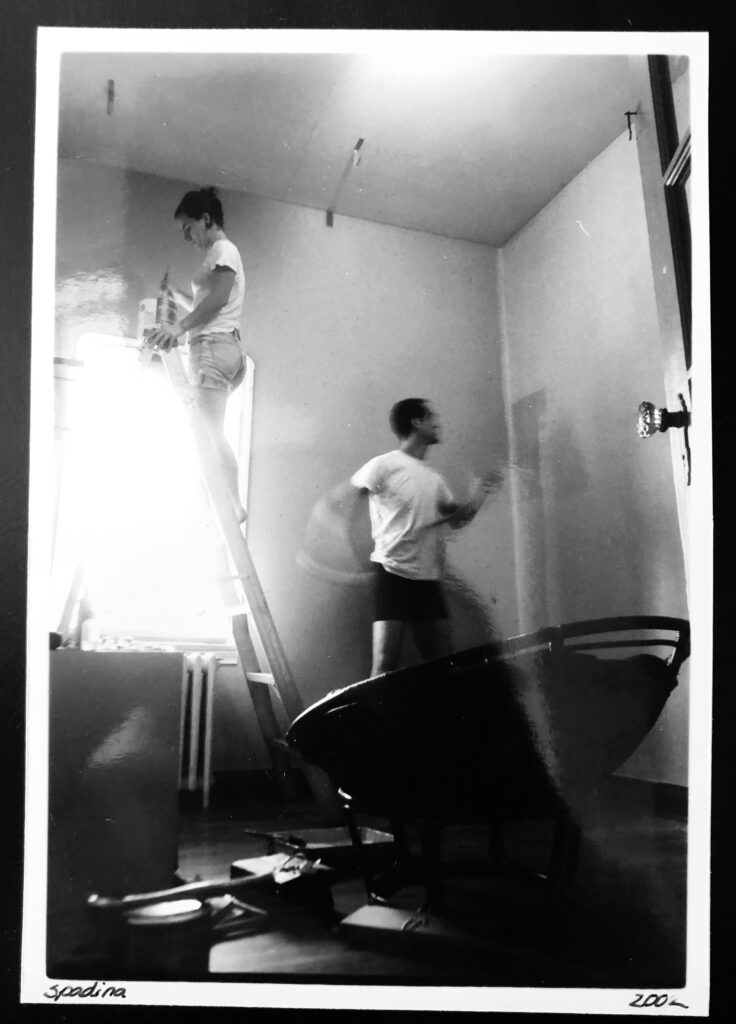

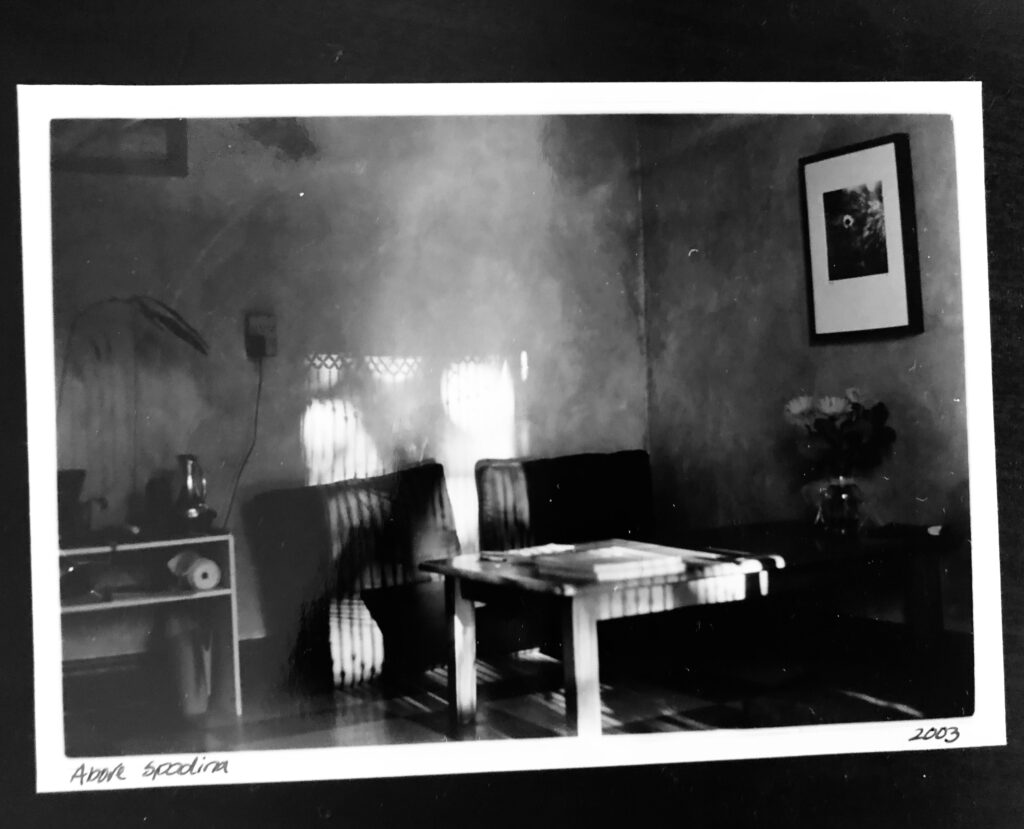

The living room was massive, with high ceilings and skylights. Sturdy galvanized pipes framed the room from above, providing a place to hang the laundry, which also served to keep the air from getting obnoxiously dry from the burning rads unaltered in their original gold. The third bedroom, nestled between the living room and kitchen, trapped all the smells of the building: mostly hot deep fryer grease, and durian. The only source of light came through an opaque pyramid of glass affixed to the roof some sixteen feet above. Before the smell in that room could be subdued, it was used as a workshop space for various projects from crafts to carpentry, bike maintenance and eventually my darkroom. There was a four foot recess that went straight up between the ceiling and the window, making the light a challenge to block. I solved the problem by constructing a foam core framed trap door that swung open and closed by a duct tape hinge. The long laundry pole was an essential accessory to the operation of the ceiling door. I would spend hours in there, bathing in the smell of the film processing chemicals which became my contribution to the bouquet of 320.

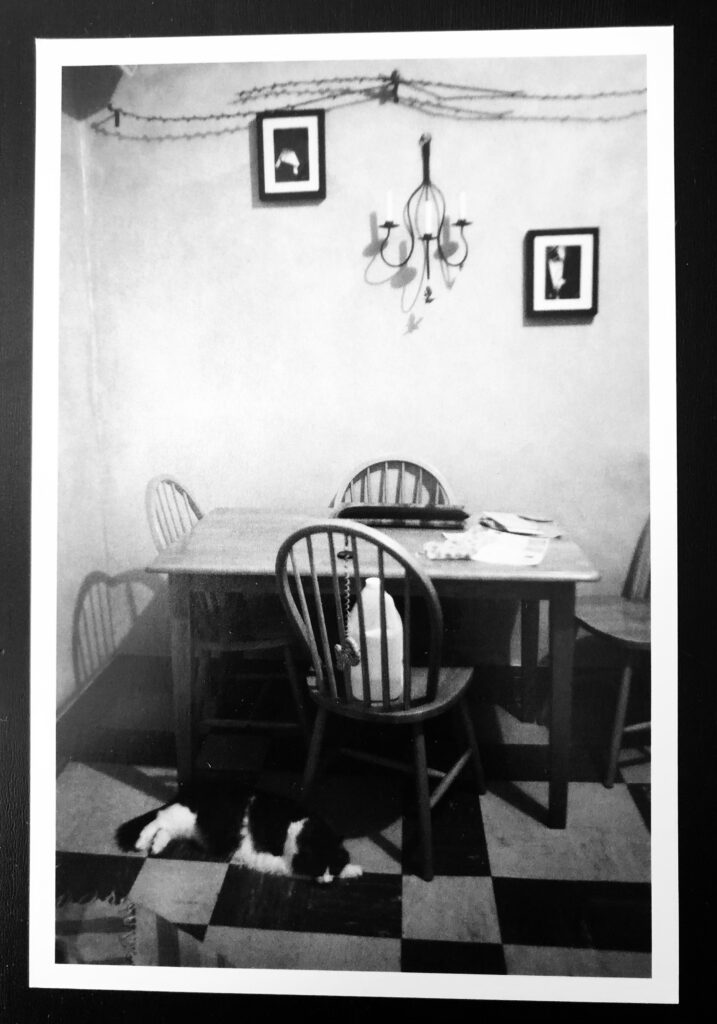

The fire escape from the kitchen led not to the ground, but to the first floor roof one flight below—the backside of Chinatown and its alleyways to Kensington Market. The small wrought iron landing was warmed by the afternoon sun and despite the constant vibrating rumble of the fans that spit out thick greasy kitchen byproduct, my potted sunflowers still bloomed. Here I savoured the first cigarette of the day before the vents sputtered and banged in acceleration toward the lunch rush on Spadina Avenue. In the kitchen if you sat quietly you would be treated to a parade of mice exiting the stove in search of any and all edible goods. In a day, over a dozen tiny spines were broken by the snap-traps that we didn’t even need to bait. This was not a solution, so the traps were discarded. You could not be negligent around food clean-up. Ever. The old washing machine was inherited with 320 and had to be manually hooked up to the kitchen faucet. The sink was a shallow but wide enamelled cast iron relic from another century. The water discharge hose was threaded through a heavy steel railroad fishplate that we stored under the sink until laundry day—I have no idea who came up with this, but it worked brilliantly.

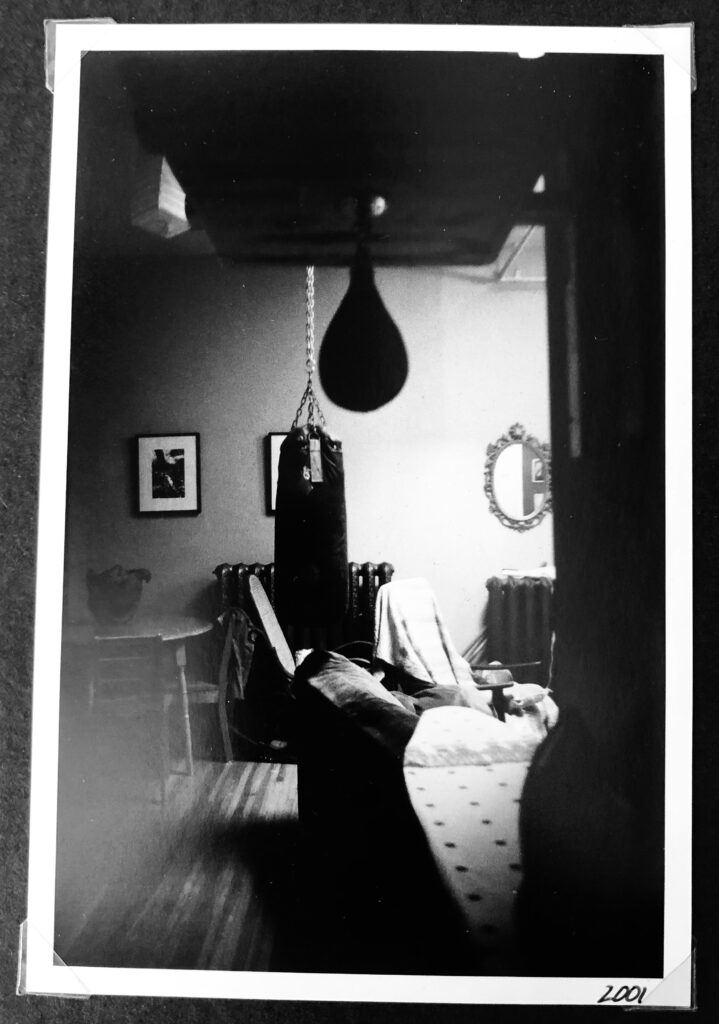

Undoubtedly the best room at 320. Note the laundry hose.

The hot water tank took up most of the bathroom’s real estate and a only slight majority of the small floor tiles were actually fixed in place. I glued photos to the bottom surfaces of the most commonly kicked floor plates. Every now and then a shriek of delight would travel through the apartment, signalling that a guest had stumbled upon one of the hidden images. The toilet never fully emptied unless you chased the contents of the bowl with a pitcher of water. I like to think the surprise photo under the floor helped to lighten the burden of toilet use at 320.

It was 1998 and I was 25–I loved that apartment. The cockroaches were the size of my thumb and 320 had a pair of shoes that existed solely for their management. As gross as it was to pop their crunchy shell and deal with the resulting explosion that could travel in any direction for up to six inches, it didn’t take long to tame the populations of rodent and insect—they stopped coming around almost entirely once my cat moved in. Sadly, the neighbours used poison, which took her life when she was just six.

The back stoop off the kitchen and my potted sunflower garden.

For seven years 320 held the space for me to transition into adulthood. I learned how to cultivate silence amidst the constant movement and volume of that time. It was the most documented period of my life. I have hundreds of photos of the apartment, neighbourhood and parties. Many are muddy and out of focus while I refined the skills that would eventually sharpen my future. I started a journal, which cemented experience through the imagery of words juxtaposed with what was fixed on film. I tried out six different avenues of employment, swapping the same number of roommates, stumbling toward the stability I craved without compromising my need for freedom and creativity. I became acquainted with grief, something that had lived within me all along, but blended with the chaos of 320 where I felt safe enough to let it roar its way out of me, joining the sounds and smells that shielded me from its full weight.

The view of Chinatown from inside the ground floor door.

Back then hauling my steel frame bike up and down the two flights of steep narrow stairs—to keep it from being stolen on the street—was no big deal. Navigating traffic and street car tracks on two wheels was the choice I made to afford my newly acquired taste for lattes over the fare of the TTC. Just now as I consider that lifestyle from middle age, I am not all that surprised to admit that I would do the same today. While so much has changed in my life since 320, many things remain. A bike is still my main mode of transportation, I write in the same notebooks, ordering the same pens from a shop on Spadina, now hundreds of kilometres away. I’ve decided it’s time to invest in a proper espresso maker and hope to one day get back to capturing more mundane moments on film.

So many memories but perhaps the forgetories* are the things that matter more.

*Of course I made that word up, but it has profound value if you really let it sink in. What does it mean? It’s all of the challenges and traumas that made us into the awesome people we are today. Those things that once weighed us down but no longer occupy space in our current reality.